In Search of Stories — Behind the Westcoaster Film

“The eastern face is rotten. It falls apart beneath your fingers.”

I was listening to an experienced mountain climber as he dreamed about about an old rugged mountain he had conquered near the western coast of Norway.

“The other side of the mountain however,” he continued with stars in his eyes. “It’s west-facing, you know. One kilometer of straight climbing, and not one rotten section.”

Instantly my mind wandered to the western fjord-ridden coast line of Norway. And I saw the dark storms; the hurricane gales bringing along a whipping sea spray, scouring clean the western cliff faces, until climbing conditions become pristine.

I might be completely wrong about why the west face is scoured clean — but about the gales roaring, and the sea rising to beat against mountain sides, I am not.

I have been in the midst of hurricane gales, braved dizzying heights, and stared out over inaccessible, bare cliff faces. And it was in this landscape the Westcoaster was conceived of.

One long beckoning coastline

The West Coast entails so much when one speaks of Norway. We’re a long, narrow country, and the coastline runs all the way from deep in the eastern Oslo fjord, around the southern tip of Norway (where I grew up) and continues all the way to the northern tip, and even beyond, wedging down south against the Russian border.

Once we Southlanders travel west, and round the south-western bend, the weather becomes wilder. The mountains steeper. The road starts needing ferries, bridges and unbelievably long tunnels to connect. And the further north you go, the more dreamlike it becomes.

I have not spent half the time I want in the fjords of western Norway, or on Lofoten, the northern protruding island cluster, famous among Norway travelers, but any chance to go there, I take.

So when my mom and I started developing a new beanie model, I looked for an opportunity to travel out there again to go and tell the story. And what a story it became!

To the West Coast in search of stories

We tell each other stories to enrich each others’ lives. When it came to bringing the Westcoaster to the public, I wanted it to come along with a story of Norwegian heritage. Or rather, I first and foremost want to tell a story of my Norwegian heritage, and the beanie is there as a tangible touch point between you and our tale.

A thick beanie to face the wild winds of the West, was the concept we came up with. And we crafted our first winter beanie — inspired by the wild weather of the Norwegian West Coast.

And here came my excuse to venture out once again. We needed a video to present the project, and I instantly knew where to go.

The iconic Pulpit Rock. On normal days, it’s full of like minded adventurers, but since we were travelling in the thick of winter, we hoped we would be alone. It turned out our wishes would come more than true, but more about that later.

First things first — a knitting mother documented

From we started Red Hat Factory, we knew we needed a brand that was as hand crafted as the beanies we knit. I want every picture, every graphic to be original content. So of course, we use my actual genuine mom for the knitting shots.

Filmed in my parent’s house, with my mom knitting a Westcoaster, this was a project for the history books.

Me and my good friend Ethan travelled from Stockholm, Sweden where we live, a ten-ish hour road trip to my childhood home on the Norwegian South Coast. We rested for a while, prepared a studio (moving furniture, decoration and lights around, getting it all right for the shots.) Then a day later the videographer arrived from Sweden as well.

We filmed all evening, trying to keep track of all the necessary shots, get the lightning right, nieces, nephews, children running around. (My mom suddenly wanting to go on an errand, and we having to deflect her.)

It was a wild ride, but it was just the beginning.

The West Coast in a day

6AM the day after, we had uncovered our cars from the heavy snow fall of the night, and we travelled the nearly 5 hours to the foot of the Pulpit Rock hike. Daylight wastes quickly in a Norwegian December, so I was a bit stressed to capture the good light before it set.

When we arrived at the parking lot (conspicuously empty) we were first met by a woman coming out of a booth and looking us up and down. “There is a man,” she said, “that walks up to the Rock every day. He says the winds are particularly violent today, and he wouldn’t recommend anyone going up. And absolutely not going out on the Rock!“

She looked us over again.

“At least you’re well dressed. If you go, at least rent some spikes.”

A few moments later, four guys (me, Ethan, videographer Simon and his cousin Emanuel) ventured up into the mountains dressed in four pairs of brutal looking ice spikes.

The hike is first on the lee side of the mountains. It wasn’t until we were near the top that the wind picked up. When we crossed the threshold of the storm, a grin spread across my face, as the wind violently whipped icy grains into my face.

The Norwegian was back in his element.

Hurricane winds and the might of the mountain

Before you go out to the Pulpit Rock plateau itself, there is one single place where you have to go past a narrow ledge. On one side a 600 meter drop, on the other a straight wall that you cant go around or up.

And this is the one spot that still haunts my dreams after this trip.

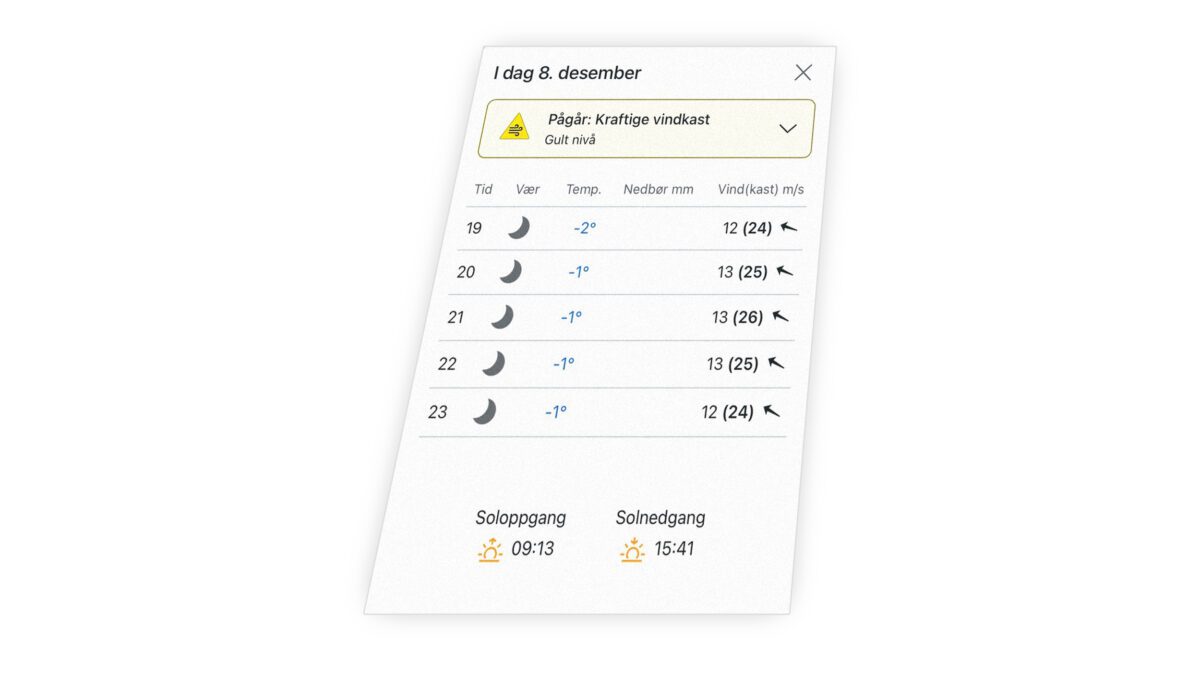

The gusts reached what we later learned were actually near hurricane speeds. And we were literally pushed around out there. But I had seen a gorgeous light on the other side of the Pulpit Rock plateau, and I wanted desperately to get out there and see.

So we moved out past the narrow point, crawled our way out and lingered.

I looked at the edge. And everything within me wanted to get out on the rock and just stare into that enticing light. There was something about the unreachability of it. The exclusiveness of the mighty mountain in a storm.

But right before I went for it, I was called back by my friends. And the chilling words that brought me back still gives me a shiver.

“If the wind picks up more than this, we’ll be stuck here.”

I knew it to be true, so we began fighting our way back. And all the while we shot footage here and there. The golden light lay over the fjord on the other side. The wild winds of the Norwegian West Coast truly blew — more than we could have asked for, and though none of our plans came to fruition, I think the film followed the script even better than planned.

And that final moment when I had to watch the others wait for the gusts of wind to die down, and leap past the narrow point — that is what still haunts me. It’s just too easy to imagine a hurricane gust pounding into my friends just at the right time, and down they go.

But we are all still here.

That same night, Simon and Emanuel drove all the way back to Sweden, spending 13 hours in the car tag teaming behind the wheel, and me and Ethan drove our 5 hours back to my parents.

We were spent! And I can’t imagine how the Swedes felt.

Epilogue — it’s not over yet

The following day we rested a bit and cleaned up the studio. Then we travelled back to Sweden. And the day after that, we all (me, Ethan, and my wife) played our instruments at a Christmas charity concert.

The only reason we managed the trip was due to meticulous planning. But no matter how much one plans — one can’t tame the mountains. And my biggest memory from this trip is the feeling of exclusivity. We fought our way up in hurricane winds, where no one else went. And we were alone, above the golden light of the fjord, knowing we were at a place and time that will never be experienced again.

And the respect for the might of nature, and how small we are when the winds pick up in exposed places, is now ingrained in my Norwegian soul, deeper than ever.